After a potentially illuminating chat over macOS Messages, I often want to access parts of the conversation. This post very briefly describes some of the functionality I require from a messaging app, and how I work-around the limitations of Apple’s Messages app.

Desired Message Reader Functionality

Ideally, I would like to be able to

- rapidly access conversations by person, date and topic;

- rapidly export conversations in RTF or OPML format;

- skim conversations by topic;

- view a summary of the conversation;

- tag individual messages according to the scheme I described in Cognitive Productivity with macOS, e.g., as a term, concept, something I don’t understand, or an action item.

The Reality

Alas, Messages does not have a concept of conversation, let alone of topic. Hence there’s no widget for exporting individual conversations. Nor is Messages able to summarize conversations. Scrolling conversations in Messages is tedious. Messages does not support annotation, let alone tagging. (Skype is no better.)

The Solution: Intelligently Named OmniOutliner Documents

My solution to these problems is to copy important conversations and paste them into OmniGroup’s “bicycle for the mind”: OmniOutliner. I can then use the full power of OmniOutliner to navigate, search for, extract and build upon key information from conversations.

Within Messages, I must manually identify the start of the conversation, select it, shift-scroll to the end of the conversation (or vice-versa) and copy (⌘C). I then create or access an OmniOutliner document, select a row, and paste the formatted text in OmniOutliner.

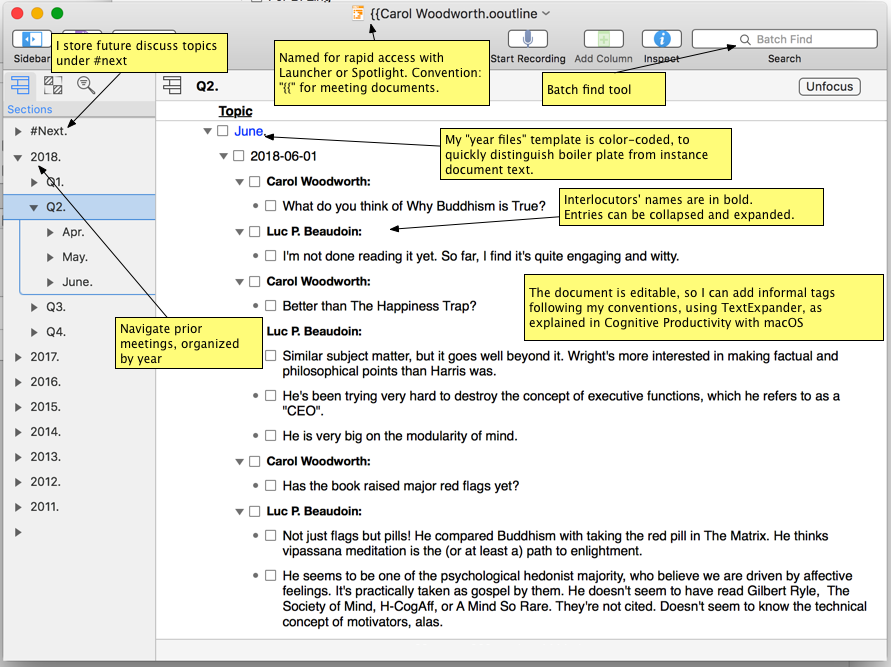

Fortunately, Messages puts a helpfully formatted representation of text in its copy buffer. The interlocutor of each contiguous sequence of messages is in bold font. Each individual message in a sequence is prefixed by a tab. Thus, OmniOutliner creates a hierarchical representation of the conversation. Below the interlocutor’s name, OmniOutliner creates one row for each message. The following screenshot illustrates a pseudo-conversation about Robert Wright’s Why Buddhism is True.

In order later to be able to rapidly access conversation files (i.e., within 2 seconds), I use a crafty naming convention: “{{NAME”. I.e., meeting minutes begin with curly brackets, followed by the name of the person or organization with whom I converse. For instance, I have a “{{Steve Leach.ooutline”. To find the file containing notes or transcripts of meetings I have had with a particular person, in LaunchBar I just need to type “{ followed by part of their name. For example by typing “{Car wo” in OmniOutliner, I immediately get notes/transcripts of my meetings with Carol Woodworth. Because on my Mac, only meeting files start with curly brackets, this convention is very effective. (Just in case some app starts using curly brackets in its filenames, I name meeting files with two of them.)

When I am having an audio meeting, I take notes in the same file. This means I can later rapidly access the minutes of meetings of most significant audio conversations I have (phone, FaceTime, Skype, in person, etc.) My OmniOutliner meetings template also has a handy “#Next” section in which I store topics for future discussions. This saves me trips to OmniFocus. More on this in future blog posts.

(Aside: Similarly, my “meta-doc” (notes) filenames begin with square brackets. For instance, I have a meta-doc file called “[Wright 2017 Why Buddhism is True”. So I can quickly access my notes about any publication so long as I remember the author and year, which my brain is very good at —very helpful for an academic.)

The copy-paste procedure described above is a bit tedious. However, if I’ve just had a 45-minute potentially illuminating conversation, the extra minute I spend copying and pasting it into my OmniOutliner document means that 45-minute conversation was not wasted. Good conversations, like other good sources of information we process, generally have more potential than we exploit.

Principle 5 of Cognitive Productivity with macOS expands on my deep _delving__ principle.