I’ve developed a structured meditation technique designed to enhance meta-cognitive control and attentional flexibility.

It’s called BSBM Meditation, short for Body Scanning, Breath, and Mantra. This approach weaves together three core practices—body scanning, breath awareness, and mantra repetition—into a single, cohesive routine. Optionally, it can be followed by a phase of reflective meditation, as outlined by Jason Siff in his book, Unlearning Meditation.

BSBM engages multiple attentional systems at once, using bodily, respiratory, and verbal rhythms to stabilize the mind and cultivate the skill of redirecting attention. This capacity to notice when your mind has wandered and to return to your anchor is foundational for emotional regulation, falling asleep, and maintaining psychological balance in the face of distraction.

The technique described here is not intended for beginners or even intermediate meditators, but rather for relatively experienced meditators. Additionally, not everyone possesses the working memory and meta-cognitive capacity to perform the actions described here. So it’s definitely not for everyone. Moreover if you are experiencing a severe mental perturbance (c., worry and rumination), you may not be able to do the technique fully but could scale it back by not trying to keep all anchors in mind; may be best then to revert to a single-anchor technique (e.g., only a body scan or only the breath or only a mantra). Also, the information below is not advice, it’s a description of a new technique.

Perhaps the closest thing to BSBM is Kirtan Kriya meditation. It is also a multi-anchor technique. Scientific research suggests that regular practice of Kirtan Kriya may have many benefits. That does not mean that BSBM does. There’s no empirical research yet on BSBM. caveat emptor applies. Having said that there was no empirical evidence on the other meditation I developed, the cognitive shuffle, before I published a paper describing the theory behind it and it.

Contents

- What Is BSBM Meditation?

- How the Practice Works

- The Role of Refocusing

- Session Duration

- Why Cognitive Refocusing Matters

- How BSBM Helps Counter Perturbance

- Theoretical Underpinnings

- Practical Applications

- Related information here about self-regulation of emotion

- Conclusion

- Footnotes

What Is BSBM Meditation?

BSBM Meditation is a structured, multimodal mindfulness practice that combines three attentional anchors: awareness of bodily sensations, regulation of breath, and repetition of a simple mantra. When these anchors are practiced together, they reinforce each other, supporting attentional stability and disrupting habitual thought patterns that interfere with calm and clarity. A fourth, optional phase—reflective meditation—may be added at the end to support deeper emotional or cognitive processing.

How the Practice Works

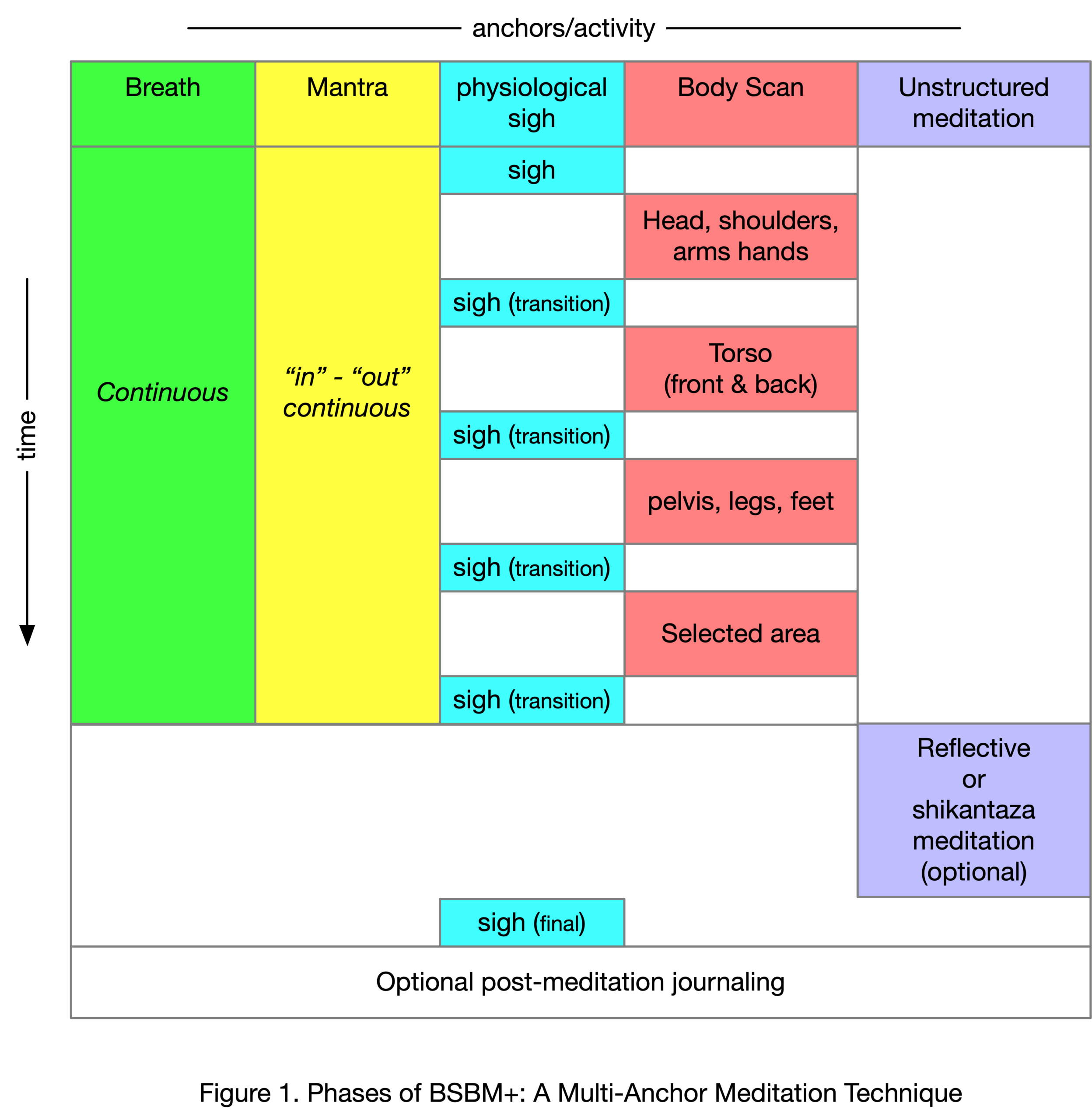

Body Scanning

You begin by gently bringing awareness to sensations in your body. This scan may proceed from head to toe or in the reverse direction. If a particular area feels hard to sense—say, your toes or fingers—you can briefly move it or simply imagine movement to bring it into awareness. Once you’ve scanned the body, you can expand your attention to the peripersonal space—the area around your body that your brain treats as part of the self[1]. You may choose to return to any area that feels particularly tense or emotionally charged.

Breath Monitoring and Regulation

Throughout the session, you maintain awareness of your breathing. Before scanning each of the three main body regions, you may insert a physiological sigh—a deep double inhale followed by a slow exhale, a technique discussed by neuroscientist Andrew Huberman. These breaths help calm the nervous system and set the rhythm for the next segment of the scan. The body scan can be organized into three groups: head/neck/arms, torso, and lower body. Breath functions here both as a stabilizing anchor and as a cue to transition attention.

Mantra Repetition

In tandem with breath and body awareness, you silently repeat a simple phrase, such as “in” during inhalation and “out” during exhalation. This repetition helps unify your internal rhythms and reduces verbal rumination by occupying the brain’s phonological loop. The mantra, though simple, serves as a powerful centering device.

Additional meditation: Reflective or Shikantaza Meditation (Optional)

If you have time, you can conclude with one of two unstructured meditations for approximately eight minutes. They are reflective meditation and Shikantaza meditation.

Reflective meditation is inspired by Siff’s approach[2]. Reflective meditation is a gentle, open-ended form of meditation in which practitioners sit without trying to control their experience—welcoming thoughts, emotions, memories, and even daydreams as they naturally arise. Unlike many traditional approaches that treat such mental activity as distractions, reflective meditation encourages exploration and curiosity about one’s inner life.

Shikantaza is a form of Zen meditation in which the practitioner sits in open, nonjudgmental awareness without using any specific object of focus, mantra, or breath control. The instruction is radically simple: sit upright, remain still, and let all thoughts, sensations, and emotions arise and pass without grasping or resisting them. Unlike other forms of meditation that involve concentrating on an anchor or analyzing mentation, Shikantaza emphasizes complete presence and acceptance of experience as it is—cultivating a direct, non-conceptual realization of reality. It is considered both a practice and an expression of enlightenment itself.

Comparing the two non-structured meditations, Shikantaza emphasizes silent, nonjudgmental awareness without engaging with or reflecting on mental content, aiming for a direct experience of reality. In contrast, reflective meditation welcomes thoughts, memories, and emotions, treating them as valuable material for post-meditation reflection and insight. Whereas Shikantaza avoids analysis, reflective meditation explicitly integrates introspection and journaling into the practice.

So, unlike the structured BSBM practice, this fourth (optional) phase invites you to allow your mind to wander freely, without correction.

Journaling

If you engaged in reflective meditation, then after the session, you may write down or reflect on what occurred during the sitting, using memory as a tool for deepening self-understanding and cultivating meta-cognitive insight. This practice integrates mindfulness with introspection, fostering emotional integration and psychological growth without imposing rigid meditative goals.

What if it’s too hard to keep 3 things in mind?

If you find it too difficult to divide your attention between three items (body scanning, breath, and mantra), you can alternate between focusing on a body part and breath. That is, you would focus on a body part (such as the hand), then focus on the mantra (“in … out”). But all the while you would mentally recite the mantra even without focusing on it.

Keep in mind that practice makes you better.

The Role of Refocusing

A central goal of BSBM is to strengthen your capacity to notice when the mind has drifted and to gently bring it back to your chosen anchor—be it the body, breath, or mantra. This refocusing act is not a failure of attention; it is the core of the training. Each return reinforces meta-cognitive control, the skill of monitoring and managing one’s own mental states.

Importantly, this constraint on attention applies only to the structured portion of BSBM. In the optional reflective phase, you allow the mind to roam without attempting to redirect it.

Session Duration

A typical session might include twelve minutes of BSBM followed by eight minutes of reflective meditation. However, the exact timing can be adapted to your needs and schedule.

Why Cognitive Refocusing Matters

BSBM’s emphasis on refocusing is grounded in a deeper understanding of how the mind becomes unsettled. One such framework is mental perturbance, a concept introduced by Aaron Sloman and myself[3].

Mental Perturbance: A Framework for Disruption

Mental perturbance refers to a state in which emotionally charged or motivationally salient content hijacks your attention and interferes with executive control. It’s not simply distraction, which may be trivial or fleeting. Perturbance is more insistent. It arises from deeper systems related to attachment, fear, or unresolved goals. It can feel involuntary and is often difficult to suppress through willpower alone.

My Integrative Design-Oriented (IDO) framework offers a way to understand perturbance in terms of how the human mind is built—how its architecture supports or struggles with regulation. From this perspective, perturbance isn’t just a symptom of distress; it’s a byproduct of how our motivational and attentional systems are designed to work.

Repetitive Negative Thought as a Symptom

A common manifestation of mental perturbance is repetitive negative thought (RNT). This includes rumination, worry, and obsession—mental patterns that persist despite our desire to let them go[4]. RNT is transdiagnostic, meaning it contributes to a wide range of mental health difficulties, including:

- Insomnia, where worry or racing thoughts keep the mind too active for sleep[5]

- Depression, in which rumination deepens negative mood and self-criticism[6]

- Anxiety disorders, particularly Generalized Anxiety Disorder, where worry becomes habitual[7]

While repetitive thought describes what we experience on the surface, mental perturbance explains the deeper architecture driving it. Without addressing this underlying dynamic, it’s difficult to fully interrupt the cycle of mental over-engagement.

How BSBM Helps Counter Perturbance

BSBM is designed to address perturbance directly. First, it anchors the mind in multiple channels—bodily sensation, breathing rhythm, and silent speech—making it harder for intrusive thoughts to take hold. Second, it trains the ability to notice when perturbance arises and to shift away from it. Over time, this builds what psychologists call executive flexibility, the capacity to reorient attention in the face of emotional or cognitive grip.

By reinforcing the refocusing loop, BSBM loosens the hold of repetitive thought patterns. This can lead to improvements in emotional regulation, reduce difficulty falling asleep (insomnolence), and enhance general psychological resilience.

Theoretical Underpinnings

BSBM draws on several cognitive and neuroscientific models:

- Global Workspace Theory (Baars), which suggests that attention is a gatekeeper for conscious experience, and perturbant content can seize this spotlight.

- Executive Function Theory (Diamond), highlighting attentional control as a key regulator of behavior and emotion.

- H-CogAff Architecture (Sloman)[8],[9] and Keith Stanovich’s architecture of mind (reflective, algorithmic and autonomous minds), computational models that illustrate how insistent motivators can disrupt cognitive processing[9].

- Working Memory Theory, which informs how BSBM targets different subsystems: the phonological loop (via mantra), the visuo-spatial sketchpad (via body scanning), the semantic buffer (all components integrated), and the central executive (via attentional redirection).

Practical Applications

The BSBM approach can be integrated into daily life or therapeutic practice. Its benefits include:

- Managing everyday stress and emotional reactivity

- Facilitating the onset of sleep, especially when cognitive arousal is high

- Enhancing focus and cognitive stamina

- Complementing therapies like ACT, CBT-I, and Metacognitive Therapy (MCT)

Related information here about self-regulation of emotion

I recently collected some tips for Regulating emotions with and without music. Many of the techniques discussed there are meant to help one switch one’s focus back from worries (and other forms of mental perturbance) to what matters in the moment.

Body scan meditation pack

mySleepButton contains an innovative pack to facilitate body scan meditation. It’s the first configurable, affective body scan. It is also the first body scan product, to my knowledge, that includes scanning the peri-personal space. Compare: Sandra Blakeslee & Matthew Blakeslee – 2007 – The Body Has a Mind of Its Own

Conclusion

BSBM Meditation is a modern, multi-anchor method for training the mind to recognize and disrupt patterns of mental perturbance. By grounding attention in multiple channels and reinforcing the habit of refocusing, it offers a practical, evidence-informed way to enhance clarity, calm, and control. Drawing from both contemplative traditions and cognitive science, BSBM provides a bridge between ancient wisdom and contemporary understanding of how the mind works.

footnotes

[1] Blakeslee, S., & Blakeslee, M. (2007). The Body Has a Mind of Its Own. Random House.

[2] Siff, J. (2010). Thoughts Are Not the Enemy: An Innovative Approach to Meditation Practice. Shambhala.

[3] Beaudoin, L. P., Pudlo, M., & Hyniewska, S. (2020). Mental perturbance: An integrative design-oriented concept for understanding repetitive thought, emotions and related phenomena involving a loss of control of executive functions. SFU Educational Review.

[4]: Watkins, E. R. (2008). Constructive and unconstructive repetitive thought: Meta-cognitive processes and emotional disorders. Psychological Bulletin, 134(2), 163–206.

[5]: Harvey, A. G. (2002). A cognitive model of insomnia. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 40(8), 869–893.

[6]: Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2000). The role of rumination in depressive disorders and mixed anxiety/depressive symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 109(3), 504–511.

[7]: Ehring, T., & Watkins, E. R. (2008). Repetitive negative thinking as a transdiagnostic process. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy, 1(3), 192–205.

[8]: Beaudoin, L. P. (1994). Goal processing in autonomous agents (Doctoral dissertation). University of Birmingham. PDF

[9]: How Many Separately Evolved Emotional Beasties Live within Us?