One of the few beneficial side-effects of the 2016 American federal elections, in which Donald Trump was elected President, is that thinking people are more aware than ever of threats to knowledge. Post-truth has entered dictionaries. We complain about fake news. We point fingers.

Assessing sources of information has always been one of the most difficult cognitive challenges thinking-people face. I discussed this topic at length in my first book. Yesterday, I published an additional chapter of my new book that deals extensively with this issue. It is the third of seven principles of Cognitive Productivity with macOS®: 7 Principles for Getting Smarter with Knowledge:

Assess Analytically

There are countless textbooks that attempt to teach readers how to assess readings. Critical reading is taught (or should be taught) at every university. There is disagreement about how effective these books and courses are. Improving how we assess conceptual artifacts requires dismantling cognitive biases, or at least keeping them in check. There are several obstacles to cognitive debiasing. As I argued at length in Cognitive Productivity, as essential as reading is, it doesn’t tend to change us very much or very quickly. The mind has “cognitive inertia”.

Whereas this chapter covers some of the same ground as other books on the evaluation component of information literacy, and it provides hyperlinks to free additional information, this chapter also contains original information. For example,

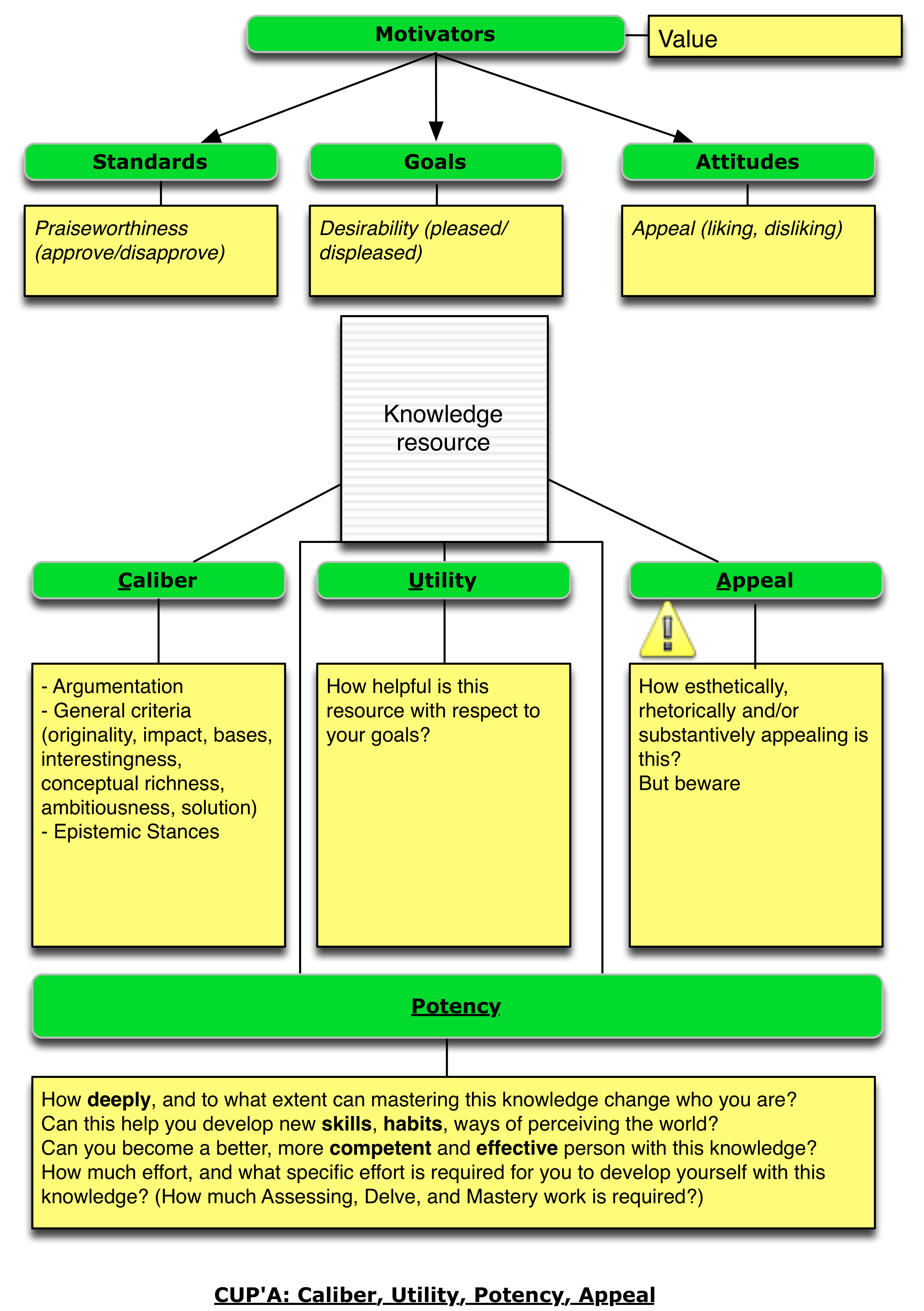

- it presents a four-factor “CUP’A” assessment schema (Caliber, Utility, Potency and Appeal), drawn from Cognitive Productivity;

- it provides screencasts illustrating how to use macOS software to implement three of the major components of CUP’A;

- it acknowledges the difficulty of changing cognitive mechanisms and biases, and addresses this through encouragement to develop monitors;

- it is presented as one of seven principles with which it is literally interlinked;

- it leverages pertinent literature that doesn’t tend to be (or has not yet been) included in courses on information literacy; and

- it is based on a broad, affective/cognitive science framework of meta-effectiveness (described in Cognitive Productivity).

The goal of this chapter is not merely to guard against the insidious effects of misinformation. It is also to help you choose sources of information, and to select those components of such documents (and other sources) with which to build knowledge, solve problems and improve yourself.

The overarching concept developed in this chapter is the pragmatic helpfulness of information.

I hope you find this chapter helpful for yourself, your staff and your students.